by Garrett Fisher

May 6, 2015

It has been happening since before most of us were born. A technological or scientific innovation is discovered, the possibilities realized, the rate of innovation extrapolated exponentially into the future, and predictions made that the workweek will drop to two days in 40 years. That was the bane of the early twentieth century, and now things have changed toward dire predictions about hacked smart homes and mass unemployment due to robots. Let’s put things a little in perspective.

Each technological improvement that comes to market presents both a reduction in cost and a new opportunity. For businesses, the cost of physical and electronic connectedness drops incrementally, improving the bottom line. For us personally, our phone bills slide a few dollars down, our cable choices improve, and we get the joys of Facebook. Apples to apples, the things available in 1980 are slightly cheaper (when adjusted for inflation) than they are now. We don’t have to drive to the video rental store, our cars last longer and get better gas mileage, airline service is cheaper and better, and we have more Chinese made products available at a cheaper cost.

From an opportunity standpoint, it is a little harder to quantify. Businesses can reach markets that they could not before. Cheaper products from Asia are available that cost more in the past. All of these things represent new possibilities in interaction that did not exist before. With the combination of incrementally decreasing costs (with some exceptions, of course) and new connectedness, the predictions begin about a robotic utopia/dystopia where we either won’t have to lift a finger or we’ll be unemployed and living in shantytowns while our lords drink fine tea in their mansions on the hill.

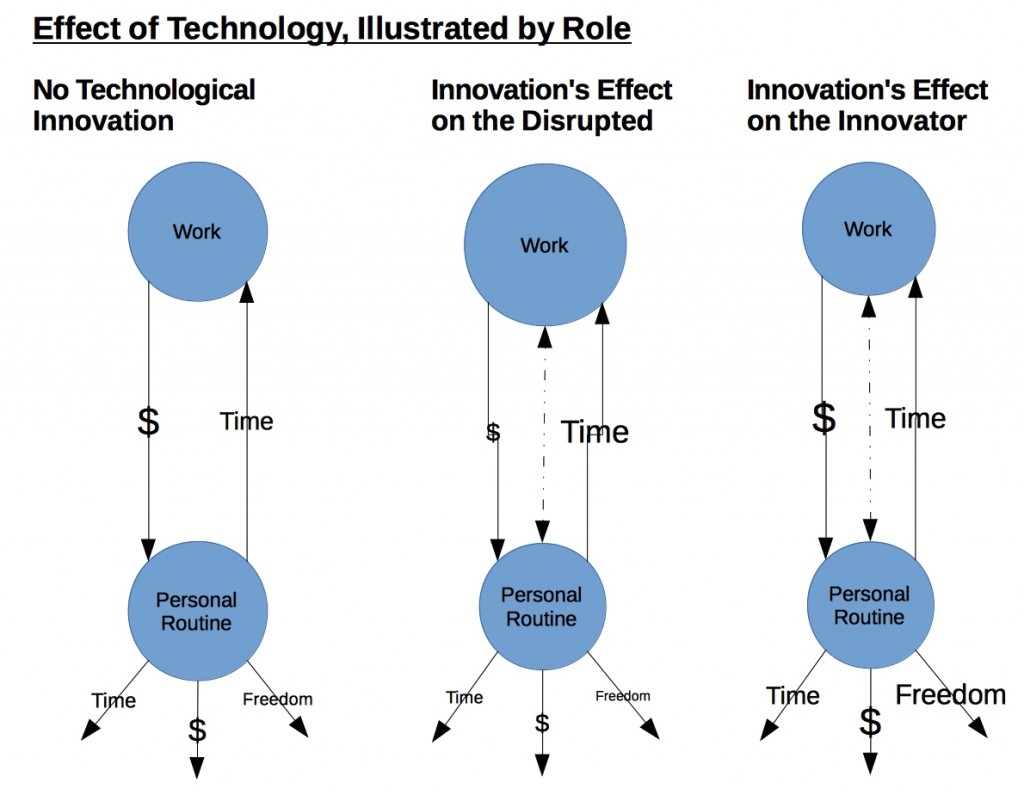

The problem is, the effect of technology is not uniform. All things being equal, with no technological change, we would all continue our career paths, earn what we earn, spend what we spend, and lifestyles would remain the same. The problem is, technology will ensure we cannot have such a stable equilibrium. As technological gains enter into society, the impact is non-uniform, resulting in the inability to make blanket assertions as to the nature of the future.

It all depends on perspective. Each innovation represents a disruption to the marketplace. Even if it is a brand new, non-existent technology that appears to threaten nothing on the market, all new innovations compete with time, money, attention span, and belief systems and must displace something. I enumerate on this concept in my book, The Human Theory of Everything. A free product may cost an end user nothing in terms of money, though suddenly we may find a person Facebooking instead of watching television. While the person saw no economic difference, his or her attention span has shifted elsewhere, Facebook benefits, and television networks suffer.

Behind these incremental changes represents two roles: those who benefit from innovation, and those who are disrupted by it. Facebook’s entire empire, including its employees at all levels, now have more economic value as a result of the attention span paradigm shift. Bonuses and compensation will flow accordingly, and their lives will improve dramatically, while also enjoying incremental benefits of technology available to society as a whole. In other words, their phone bill drops 4.2% this year and their compensation goes up an extraordinary percentage. Meanwhile, at a major television network, ten percent of the broadcast antenna engineers and maintenance workers lose their jobs. Their income drops dramatically, and may not be replaced in the present field, yet they also enjoy a 4.2% drop in telecom costs.

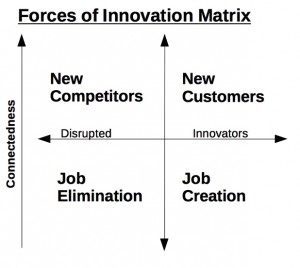

Some have said that capitalism, in its drive for productivity and innovation, is a zero sum game. Maybe it is; I am not in a position to render a formal opinion on it, as I do not have the data as to how many jobs are created vs. disrupted in the innovation cycle. Logic has it that the less we need people due to technological efficiency, the more so things look like a zero sum outcome. It’s ultimately a matter of job creation rates from innovation measured against job elimination rates resulting from disruption, adjusted according to population change percentages (births minus deaths).

The faster we innovate, the more this disruption takes place. More high-earning innovators are created, and more existing jobs are disrupted, all netting to an outcome pursuant to the underlying job rates each activity creates. There is a transactional cost to the changes associated with innovation. Each job that is disrupted where the person successfully migrates to an innovating field still requires retraining time and cost, and often comes with the tax of a foreclosed house or vanquished retirement savings during the transition period. Innovation is not as seamless as some would prescribe. There is also the factor that the process of building innovation – i.e., building out new technology and implementing it, involves substantial capital, creating a temporary stimulus. Recall our social media examples and think of the exorbitant amounts of capital poured into publicly-traded social media companies, all while we are not sure if they even have a revenue model for the product. All of those billions spent represent a stimulus to the economy, which can create the false illusion of permanent job creation, when it is merely the flow of stored capital into the creation of new infrastructure. Time will tell what income that infrastructure will produce, and we may find that we have innovated in areas we do not need, where that infrastructure will be abandoned, an ultimate economic loss.

The other factor is that innovation increases connectedness. Connectedness means more and different market participants, resulting in competitors that did not exist in the past (for example, the Chinese worker who now has your manufacturing job). These connected competitors push prices down, resulting in incremental benefits to all (cheaper Chinese goods for everyone), with yet again, higher disruption rates as things change faster and faster, now with the combined forces of new technology changing industry and new technology bringing more competitors to the market. Connectedness also brings new customers. The final adjudication as to who that process benefits depends on job creation and elimination rates, isolated from the perspective of who is affected. Some countries prosper, some decline as do some industries and some companies share similar fates.

The fact of the matter is that increased rates of innovation relate to increased rates of disruption. Journalists love to declare that the result will be either utopia or dystopia, and the reality is that those are the two maximum end points within the range of options. More than likely, we will continue a path down the middle, with more employment volatility than ever, within industries and between countries. My advice to stay relevant is to adopt a plan of continued personal growth and skills development, and let go of the antiquated idea of spending one’s entire life in the same career. Those days are gone.