by Garrett Fisher

April 5, 2014

The Citizens United verdict handed down by the Supreme Court in 2010 was one of the more controversial rulings of the SCOTUS in recent years with continuing ramifications to expansion of corporate rights. The Supreme Court cross-referenced juridical personhood – i.e., that corporations are people legally – and applied first amendment free speech rights in deciding that corporate political contribution limits cannot be imposed separate from individuals. Prior to the ruling, corporations had stricter limits on campaign contributions than individuals did.

Before expressing my thesis on the ruling and its effects, it is imperative to point out the nature by which SCOTUS operates compared to the rest of the government. Justices have lifetime appointments – and the only political influence in the process is at appointment time from the President and through Senate confirmation. After that is done, politics is out except for the personal views of each justice. More importantly, each justice writes an individual opinion on his or her ruling – whether favorable or dissenting. Unlike other rancorous and child-like sections of government, justices are intellectuals that write tremendous verbiage substantiating the ruling – from citing legislation to case law to the Constitution.

That being said, I personally enjoy the process of watching how the Supreme Court operates. Like everyone who has a brain on this planet, I cannot agree with every decision – or for that matter – even why. Nonetheless, the decisions are put into writing with healthy backup into the public record. Ideally, more of the government would be required to operate in such a way.

The Citizens United case is missing some key legal components of its argument. As I do not like politics or political rancor, I will stick to the legalities. Whether or not corporations “should” be entitled to free speech is a matter for the people to decide. However, the principles embodied in the ruling fall short of the reality that the ruling would impose into society.

A logical question about corporate free speech is “who is speaking?” Shareholders own the company and exercise, in a very loose and disconnected way, final authority on matters of governance. Generally, shareholders vote for Board seats and on significant stock transactions. The company exists to further the financial interests of the shareholders. Some shareholders purchase stock for control and strategic purposes – not just entitlement to their share of profits; rather, the desire to influence the outcome in light of other financial holdings the person may have. The Board of Directors oversees the company broadly and hires management to run it. In the end, the corporation should “speak” for the shareholders – their financial and strategic views.

An ensuing question is how well this entire process works now that campaign contributions have been brought into the question. Does the process allow the “voice” of the shareholder to be expressed in free speech – particularly with how campaign dollars are spent? Following the money in the case of political contributions leads us to an answer. The legal principles of corporate free speech apply across the board; however, this case allows for an interesting test subject.

It is critical to specify which corporations we are speaking of. Private and closely held corporations are one thing – where investment is optional, bylaws are negotiable, and most investors cannot invest unless they are “accredited” – which is a securities regulation ensuring that the person investing is sufficiently wealthy to know what they are doing. If free speech is limited by investment, the principles of current law assume that the investor is smart enough to either know about it or influence it. The argument in this article largely applies to publicly traded companies as common people own them and the law provides an abundance of requirements on management and executives requiring shareholder interests to be honored. Those shareholders are protected in many ways; hence, it would be logical to expect free speech to apply to public shareholder protections.

That being said, is the shareholder of a publicly traded company having his or her “voice” heard in corporate free speech? My answer is a resounding “no” based on the ecosystem of corporate governance.

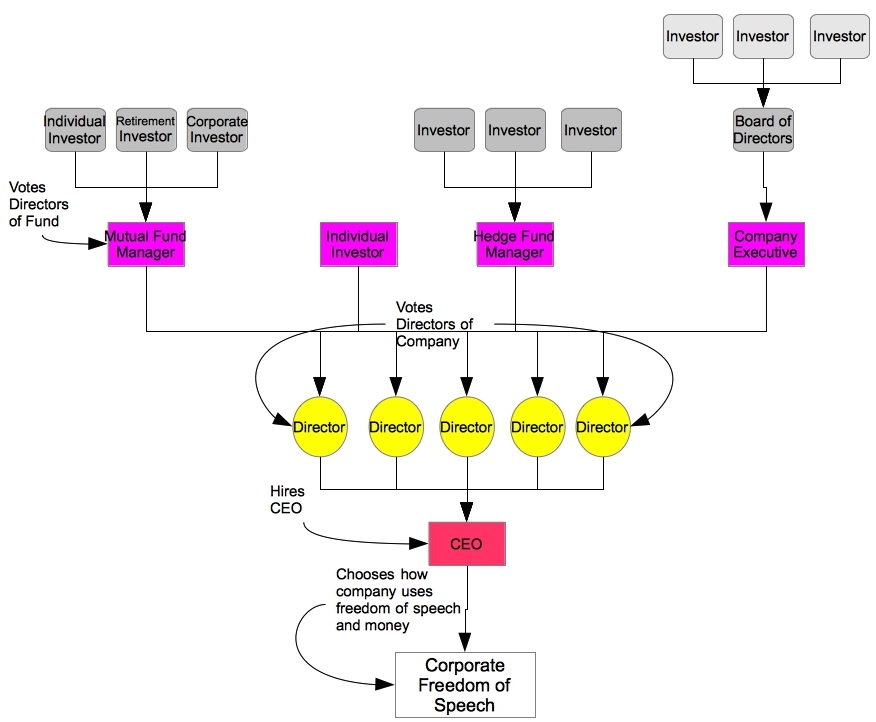

For the simplest view, an individual investor buys stock in a publicly traded company. What are his or her rights? To receive reports of company performance, attend shareholder meetings, possibly propose a vote at said meeting, to vote for the Board of Directors, and to vote on any other matters the company bylaws, government regulations, or laws require shareholder approval for. Political spending and other free speech is not one of those things. Shareholders effectively vote the Board – and the Board hires a CEO and other executive management. Those managers decide company budgets and how to spend political dollars. The Board has a say – if they choose to get involved.

Notice that there are 3 layers from the shareholder to corporate free speech. At every layer, the shareholder loses his or her voice and other opinions get introduced. For mutual funds, another layer is added. Mutual funds are the primary vehicle for individual investors and especially retirement funds. The mutual fund shareholders have the right under federal securities regulations to vote for the Board of the fund who, in turn, chooses a fund manager. The mutual fund votes the shares in its possession. For hedge funds, the limited partners cannot even vote the hedge fund manager out and have fund withdrawal restrictions – allowing the fund manager to vote shares and possibly for a period for which the investor wishes to leave the fund. In the case where another public or private company purchases publicly traded stock (done mostly for strategic business reasons), this whole layer is doubled in size. Shareholders have next to no voice in corporate free speech.

One may argue that the corporation exists to make money and, if the free speech is exercised to do so, the obligations of the corporation have been meet. Legally, that is the case – and that is the problem. Ethically and principally, companies don’t do just anything to make money – they have a product suite and a mission and limit activities to a sphere around both. Further, a discerning and reasoning individual can see personal views of CEOs being expressed in the publicly on all sides of views. How could the most opposing views both be good for business at the same time? A sensible explanation is that the views of the executive are coming into play and said executive is using the public company as a platform for personal views.

The Supreme Court failed to recognize the broader legal implications of reality in its ruling. While it did apply First Amendment rights to juridical persons, it did not look at the labyrinth of state laws, federal securities laws, federal business laws, securities regulations, bylaws, and case law at play for public companies. State laws govern the basic structure of corporations. Securities regulations are mountainous. Those realities impose the shareholder/Board/management dynamic that exists today. Simply adding a naïve, idealistic concept that corporations are people and “it will all work out” constitutionally fails to consider that the very constitutional principle embodied in the ruling is completely impotent. It will require another SCOTUS ruling or strong legislation to make that happen.

Corporate free speech is not as simple as earning a profit. Shareholders have varying levels of concern for the environment, for the disadvantaged, quality of products, location of operations, and for whether or not the company should take a short or long-term view to profitability. Economics, in its rawest sense, cannot answer those equations, as they are an expression of the freedom of individuals and how they choose to think. When it comes to matters outside of pure profitability, the same corporate governance mechanism discussed earlier in this article applies and fails to create a voice for the shareholder – not only political contributions as discussed in the Citizens United case – also corporate charitable contributions, and philanthropic motives (such as fair trade).

A proper consideration that the Supreme Court failed to consider was reality on the ground with the ruling. The Citizens United ruling, in practical application, will place an inordinate concentration of free speech on corporate executives – individuals who are hired employees and may or may not own any stock in the company they are speaking for. In reality, the ruling increases obfuscation of free speech – the very principle the ruling was based on.

Whether or not corporations should have free speech, well, that’s for politics to battle it out.